Bill Stewart remembers The Hydrostone before the short-term rentals arrived. He and his partner, Mary Reardon, have called the north end Halifax neighbourhood home since the late 1990s. It’s always had its charm, he says: English-style row homes open onto wide, treed boulevards of Norway maples and European lindens. Gardens teem with flowers; conversation spills from front porches. The neighbours—a mishmash of families, recent grads and retirees—are friendly.

“It’s a nice area we have,” he tells The Coast.

It isn’t all that surprising that The Hydrostone would attract its share of tourists too, but the effect that’s had on the community is another thing. Stewart and his neighbours have watched as home after home in their historic neighbourhood have turned over into short-term vacation rentals—and it’s happening elsewhere in the HRM too.

File photo

Hydrostone resident Bill Stewart has watched his neighbourhood change from families and retirees to short-term rental homes.

And while the change has brought its share of inconveniences—from noise, to late-night disputes and police calls—Stewart worries most about what he calls a “hollowing out” of the neighbourhood: Properties that might have housed one, two or four families 10 years ago are being bought and converted into vacation rentals going for $200 to $300 a night. And it’s pushing would-be renters and homeowners out.

“If you’re looking for some place to make your home for the next year or two or more, you’re not gonna find it,” Stewart says.

It’s an issue Halifax regional council has known about—and debated—for years. Last Tuesday, HRM councillors once again bandied about regulating Airbnbs, VRBOs and the like, only to decide—as councils so often do—that they needed more data first. (“My concern is we’re going to set ourselves up for a whole lot of headaches,” councillor Shawn Cleary, who spurred the drive to defer council action, told his colleagues.)

The unhurried pace bothers Stewart. He worries council’s inaction could set a much-needed bylaw change back years, instead of months. And in the interim, Haligonians in search of housing are increasingly feeling the pinch.

A growing trend

According to AirDNA, an aggregate report of short-term vacation rentals listed on both Airbnb and VRBO, Halifax boasts 1,670 active listings as of December. More than three quarters of vacation homes currently for rent in the HRM are listed as “entire home” rentals—and over half of those units have two bedrooms or more. Meanwhile, 734 Haligonians had nowhere to sleep on Dec. 13—and that number, according to the Affordable Housing Association of Nova Scotia’s “by name” list, has nearly tripled since 2019.

The reason there are so many short-term rental listings is simple: It’s good business if you own property. Per AirDNA, the average short-term holiday rental in the HRM goes for $136 a night ($163 in the summer months) and is booked for 77% of its days on the market. In a 31-day month like December, that adds up to $3,246 in booking revenue before expenses—and there are dozens of properties listed in the $200 and $300 range. Pit that against the going rate for a one- or two-bedroom apartment ($1,957 and $2,296, respectively, per the latest Rentals.ca report), and it doesn’t take a business degree to choose a winner. Plus, you can raise the rent and ditch tenants anytime you like. Forget decency or Tim Houston’s pesky 2% rent cap.

The deal is so good for landowners that, like other tourist cities and towns in Canada, it’s become a quasi-annual event in Halifax: The inevitable late-May, early-June move many renters are forced into when their lease ends and their landlords want to clear room for tourist season. Last summer in Lunenburg, Global News reports, lifelong South Shore resident Jessica Smith found herself and her family resigned to living in a tent after their fixed-term lease ended. Despite her full-time job in health care, they couldn’t afford the higher summer rates. On Canada’s opposite coast, the phenomenon has its own moniker: The “Tofino shuffle.”

Charlotte MacDonald had her first brush with the Halifax equivalent last summer. She’d had her Chebucto Road bachelor suite for three years, but her landlord told her in July that she was “going in a different direction.” Within days of MacDonald moving out, a friend who lived in the building texted her an Airbnb listing: Her old apartment was listed for $210 a night. In a six-unit apartment building, MacDonald told The Coast in October that four units had become Airbnbs.

Photo provided.

Charlotte MacDonald in her Chebucto Road apartment.

While it’s harrowing for renters, it’s perfectly legal. There are no laws in Nova Scotia requiring a landlord to extend a tenant’s lease, even if the tenant pays their rent on time and keeps the place tidy. If a landlord wants a tenant to leave at the end of a fixed-term lease, “they’re not obligated to have a reason,” Dalhousie Legal Aid’s Katie Brousseau told us in the fall.

“It makes it very difficult for folks on a fixed-term lease to know whether or not they’ll have a continued tenancy.”

Municipal change

Caora McKenna

From HRM study on short-term rentals

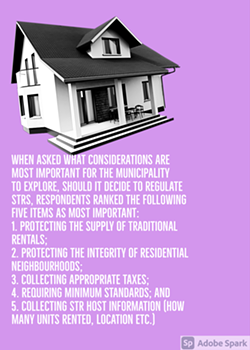

Halifax regional council is well aware of its housing crunch. The HRM has been working toward a bylaw regulating short-term rentals since 2019. That May, the community planning and economic development standing committee directed HRM staff to gather public input into how Halifax should handle Airbnbs and other short-term rental properties. The community’s response was resounding: More than 4,000 people responded—a record for council surveys—and 80% of them, according to HRM planner Brandon Umpherville, “were critical to short-term rentals in some way.” Two in three respondents agreed that in residential neighbourhoods, Halifax should only permit short-term rentals where the host lives in the same residence.

As Halifax’s proposed short-term rental restrictions go, HRM principal planner Jill MacLellan told councillors on Dec. 13, the region would fall “on the more permissive side” of how municipalities have regulated services like Airbnb and VRBO. Regional council favours restricting short-term rental properties in residential areas by limiting them to a host’s primary residence. But Halifax has taken a hands-off approach to short-term rentals that operate in areas where hotels are already found (i.e. downtown). Other Canadian cities have taken a harder line: Markham, Ont. has effectively banned short-term rentals since 2018. Toronto allows short-term rentals, but only in a host’s primary residence. “Whole home” rentals are capped at 180 nights a year. Quebec City and Mississauga, Ont. have similar restrictions.

Stewart says he’d like to see HRM council “make some clear principles” on how it will handle mixed and commercial zones, where some condo buildings have turned into “ghost hotels.” Halifax may tighten its restrictions once a bylaw is passed—there’s been provincial talk of taxing short-term rental properties the same as hotels and other tourist accommodations—but first things first, the HRM needs a bylaw.

Regulation challenges

As Halifax plods toward a bylaw change, Nova Scotia’s government has been working on its own measures to curb short-term rentals: Starting in April 2020, the province announced it would require hosts to register their properties, unless they also lived in the home they rented. (That requirement has since been expanded to include hosts who rent out their primary residence. The new legislation comes into effect in April 2023.)

Communications Nova Scotia

Under premier Tim Houston, Nova Scotia’s government has expanded its Tourist Accommodations Registration Act to require hosts who rent out their primary residence to register their properties annually.

Under the province’s plan, hosts will pay an annual licensing fee of $50 or $150, depending on how many bedrooms they’re renting. Anyone caught without a license can be fined up to $7,500 a year.

But rather than spur council forward, the dual-action has led to confusion (and some degree of finger-pointing): Which level of government is taking the lead? Who’s on the hook for enforcing any short-term rental bylaws? And how successful can a province-wide registry be at catching hosts who flout the rules?

Councillor Pam Lovelace shared her doubts last Tuesday, telling her council colleagues that Nova Scotia’s plan “looks great on paper,” but there are new rental platforms “popping up all over the place.” How could the province or the HRM stay on top of under-the-table listings on Reddit or Facebook Marketplace? Fellow councillor Shawn Cleary worried that in clamping down on the unsanctioned short-term rental market, “little mom and pops” who “rent a few bedrooms” would be caught in the crosshairs. He motioned for council to refer the issue to the committee of the whole for more discussion. Cathy Deagle Gammon, David Hendsbee, Trish Purdy, Tony Mancini, Iona Stoddard, Tim Outhit and mayor Mike Savage agreed.

(It bears mentioning that each of the council members who voted to defer action also own their homes. Two in five Haligonians surveyed in Canada’s latest Census do not.)

There’s merit to Lovelace’s concerns, but good evidence to suggest Cleary’s worries are misplaced. As we reported in 2018, more than half of Airbnb rentals in Halifax were owned by hosts with multiple listings—hardly the “mom and pop” pensioners Airbnb loves to portray as its base and Cleary wants to protect.

Part of Halifax’s dragging its heels has stemmed from a drive to protect its tourism industry. (Per Discover Halifax, tourism brings the HRM about $1 billion in direct spending a year. Taking accommodations off the market could spoil the golden goose, some councillors worry.) That’s not enough to outweigh the need for housing action, councillor Waye Mason told his colleagues.

“I know this will be a pain for tourism, and I know this doesn’t come without an impact on that side—but I think the housing crisis is acute when you start to go by any of the stuff we’ve been talking about, the tents in parks and all that,” Mason said on Dec. 13.

He argues there are “hundreds if not thousands” of units that would return to the rental market if Halifax brought a bylaw into place sooner, and there’s data to back him: A 2019 McGill report found short-term rentals had taken as many as 740 housing units off the region’s long-term housing market.

Legislation limbo

Council’s decision to bring the HRM’s short-term rental dilemma to a committee of the whole meeting—instead of straight to a public hearing—means any legislative changes won’t come, in all likelihood, for another year or more.

Principal planner MacLellan told regional councillors that if they wanted further staff reporting to guide an eventual decision, it would be “six months to a year” before that report would be ready. Mayor Savage pushed back, asking regional planners for “whatever you have” by Apr. 1, 2023.

That’s too long for Stewart, who fears it will only delay municipal action that could be implemented today.

AIRBNB

This ghost hotel in the Hydrostone was built to be a nice place to visit, with three separate “entire home” units.

“Here we have the province,” he says, “who has a real focus on tourism, and they’ve decided to give housing the priority over tourism—at least in their approval of the Tourism Accommodation Registration Act… The sad part is that mayor Savage and a few of those councillors last Tuesday did not seem to have that same priority.”

In the meantime, Stewart looks around at his Hydrostone neighbourhood and wonders what the future will bring. He’s already heard from younger neighbours who can no longer afford to rent or buy a home. He worries for them—and for the rest of his city.

“Housing is a real crisis here,” he tells The Coast. And the heart of it isn’t contained in staff reports or deferred committee meetings.

“It’s right outside my door. It’s right next to my wall.”

—With files from Matt Stickland and Sandra C. Hannebohm